A macroaccounting of the August 2020 financial crisis.

In my State of America 2020 post, we went over the many layers of existential crisis America is currently facing. The most pressing one is the economic issue. I wrote:

The next big area of concern is the economy. I actually studied economics in college, and I'll be the first to tell you that most of it is over-wrought academic mumbo-jumbo. What ultimately matters is that the job-money-rent-food cycle continues "working" for most* citizens. Very serious threats like hyperinflation / devaluation of currency, or mass defaults of households and businesses are now on the horizon. When James Carville said "it's the economy, stupid", he was referring to this; if most* people cannot sustain their livelihoods through the economic system, and order cannot be kept through the judicial / military system, that's when the zombie apocalypse starts. Nobody wants the zombie apocalypse to start.

Well, it's been about a full month. I am unhappy to report that the zombie apocalypse unfortunately seems closer than ever. Alex Jones is probably wondering what seasoning goes best on his neighbors.

I'm joking, of course. Kind of. Here's a brief recap of our economic situation, as of July 31:

- Only ~43% of Americans have some kind of job

- ~18 million Americans remain officially unemployed (U3)

- Another 100 million Americans are categorized as Not In Labor Force

- Another 71 million Americans are not "Officially Employed"

- Among those 43%, it is unclear how much income they're actually making. You are counted as "Officially Employed" if you:

- Work 1 hour / week

- Are temporarily absent from your job, whether or not you are paid for time off

- Worked a minimum of 15 hours without pay for your family's business

- According to some surveys, as many as 69% (nice) of Americans have less than $1,000 in savings. (And those are 2019 numbers; it seems safe to assume the % is substantially higher in July 2020)

- The Paycheck Protection Program (extra money for workers) ended on June 30, and the CARES act (additional unemployment benefits) will end today. It seems overwhelmingly likely that additional major stimulus will have to be passed to keep Americans afloat.

- In April, the CBO projected the year-total US deficit for 2020 will be $3.7 trillion dollars (larger than the entire US debt in 1991) -- before we pass any new stimulus.

- GDP shrank ~10% in the first half of 2020 (from $21.43 trillion in 2019, to an annualized $19.41 trillion now), and although it's expected to bounce back substantially, everything is up in the air due to coronavirus uncertainty.

- Current US debt, before any new stimulus gets passed, is $26.48 trillion.

- This puts us at 136% debt-to-GDP (123.6%, if you want to be super fair and use 2019 numbers). This is highest in American history, well surpassing the WWII peak at ~122%

- According to pgpf.org, a whopping 39% of current US debt is held by foreign creditors.

Everyone seems pretty fine with additional major stimulus (me included). But why should we care about the debt?

A very common refrain from many pundits, especially post-2008, is that public debt just doesn't matter anymore. The fed can print* as much money as it wants, and as long as there's no detectable inflation, we shouldn't run into any issues. There's a pseudointellectual theory of economics called Modern Monetary Theory which makes a garbled academic case for this point, and there's been a lot of handwringing about it. To save you the trouble; the whole thing is hot philosophical garbage.

I actually think there's value in it, though, from an absurdist, Modest Proposal-esque troll on the establishment of fiscal politics. As stated in my civics series, the 2008 bailouts basically shattered any sense of justice or reason that legitimized our economic system. If we can just print* trillions of dollars to save big banks and corporations, why can't we just print* trillions of more dollars to fix healthcare, education, and alleviate economic inequality?

The 20th century macroeconomic models fail us here. While the classical views on macro were mostly debunked by 1973, it really took until 2008 for the entire system to stop making sense completely. And by 2020, we're fully swimming in the theater of the absurd, as this domain of financial sophistry comes head-to-head with the real livelihoods and raw survival decisions of millions of American families.

I still think there's hope for us to make it through; avoiding a dark age, civil war, zombie apocalypse, military dictatorship, or some other kind of terrible calamity. Mostly, we just need to agree about basic facts and ideas about how the economy works, and then collectively reckon with how out-of-sync our financial system is with the material needs (and wants) of US citizens. Then, we need to elect leaders and agree on policy proposals that both clearly outline a shared future vision for the American economy, and then take whatever necessary steps to get us there safely. All while unifying around rising foreign adversaries that want to divide us, like Russia and China, and -- preferably -- taking meaningful steps to actually address centuries-long racial and economic disparities that have plagued the American populace since its inception.

Should be easy, right? 😅

I offer nothing in the way of specific answers, platforms, or policy proposals; I am not an economist, historian, or policy guy, and I'm not technically an academic of any kind. I formed most of my perspective on the economy from watching documentaries like I.O.U.S.A., movies like The Big Short, and reading books like The Ascent of Money, The Age of Turbulence, and When Genius Failed. I disliked most of my own college curriculum (I did study economics for a year or two, before switching to computer science, before dropping out). So take all of this with a grain of salt, and cross-reference my claims with people who actually know wtf they're talking about.

If you feel like you're totally and completely lost on the subject of economics, and you've been persuaded to take civics seriously, I highly recommend jumping into the history and contemporary debates about it. Trust me; the water is fine. I think a lot of young people lack the confidence to understand or participate in this discussion, because they think it sounds complicated, involves a lot of complex math, or is probably best left to "experts". While it might not be for everyone, I assure you that these concepts are truly not that hard to understand. You don't need any math beyond basic arithmetic, and there are many accessible entry points into the history and politics stuff (the aforementioned I.O.U.S.A. documentary is a great place to start; there's even an Ascent of Money TV show). If anything we discuss doesn't make sense initially, just go slow and Google things.

The outline of this essay series is simple. I only keep track of two metrics regarding the US financial system: the debt-to-GDP ratio and the PPP / exchange rates of the US dollar. To break this down further, we'll look at three topics in total, split into three different essays:

- Not all debt is created equal

- Not all GDP is created equal

- The power of the USD

This first essay is about debt.

===

Debt

Everyone understands the basic idea of debt; you borrow money from someone, and you incur a financial obligation to pay them back eventually. That's the most we can say about it definitively. Debt is a truly fascinating subject; there are multitudes of different theories about it, types of it, and personal experiences with it. I can't hope to do the concept itself justice, but I'll certainly offer an abridged take. The way I frame it is like this:

Debt is a financial relationship (between humans, business entities, governments), which is mediated by both other types of relationships (personal, familial, commercial, civic) and is enforced by specific systems (the legal system, international agreements, physical force). The nature of this relationship is inherently contextual; the interpretation of what a debt means depends highly on the specific parties involved, the surrounding cultural / legal environment, and even the global background setting of world affairs. Debt itself is mostly neutral; it can be used positively, it can be used harmfully, it can be used for growth, and it can be used for control.

A useful way to break down different types of debt is to examine expectations around repayment, interest, and consequences for defaulting. Let's look at some toy examples, just to get a feel for the different varieties here:

You owe thousands of dollars to a 1920s mafia gangster (maybe you took on a gambling debt, or you owe money for "protection"). You better have his money by next Thursday, or "it'd be a shame if somethin' happened to ya'" (he's going to break your legs, burn down your business, hurt your family, etc.)

Your dad loans you $3000 to buy a used car upon graduating high school. Most dads probably don't care when you pay it back, or even if you ever do. Maybe, if he's a jerk, he'll tease you about it often at family gatherings.

You recently lost one of your three jobs. To buy food / diapers for your kids, pay rent, and cover your costs for the next month, you take out a payday loan at 350% APR. If you're very lucky, a family member / local church organization chips in to pay it back quickly. In the dismally common case, you just can't pay it back for a while, so your principal balloons to unpayable proportions. You just live in a debt trap; your credit score tumbles, monthly payments rise, and your assets / wages are at risk of foreclosure / garnering. If you're lucky, you find a social worker or charitable lawyer to negotiate with the company to write off some of the principal.

You take out a student loan via FAFSA to go to college, at a 9% interest rate. You go to a modest school, and only end up racking about $50,000 in total. You're able to get a decent job afterward, but you avoid paying it off until you're stable and have a healthy amount of savings. You plea forbearance several times, but eventually, the interest starts to accrue. You notice that total outstanding student debt for US students exceeds $1.6 trillion dollars; nobody is actually sure if you'll ever even have to pay it back, and major presidential candidates campaign on forgiving it entirely. Your credit score is weirdly fine.

These examples illustrate just how differently debt can function, depending on context. And it varies even more greatly between countries, cultures, and across the history of human civilizations.

The history of debt is rich, and very much worth learning about. The core ideas about it stretch back to the dawn of human civilization (as early as 3500 BC, clay tablets in Mesopotamia were inscribed with promissory notes), and theological debates about issues like usury are as old as religion itself. You can truly spend a lifetime studying it. I won't get into the history here, but I'll re-up the aforementioned Ascent of Money book by Niall Ferguson as a great starting point.

In modern capitalist economies, debt has a precise technical definition. It is a financial construct, typically backed by a legal contract, containing some universal components:

- The principal is the amount the debt is for. (If I take out a loan for $1,000, the principal is $1,000)

- The interest rate is a percentage of the principle that is accrued over the lifespan of the debt. The accrual period can vary; interest can accumulate monthly, yearly, cumulatively, or some other defined period. For a $1,000 loan with a 5% monthly interest rate, after one month, you owe $1,050 in total.

- The repayment terms describe things like the length of the loan, late fees, legal arbitration, and consequences for default. They can get complicated and varied depending on the specifics of the loan agreement.

Issuance, management, and repayment of debt is central to the functioning of all modern economies, at every level of commerce and civics. As such, economies across the world have racked up epic proportions of debt, both private and public. At the heart of global commerce is a simple question: Is having all of this debt a bad thing?

The answer, of course, is: It depends. Some debts are wise, and other debts are unwise. You have to look at each one specifically. Luckily, we have a lot of them to go through :D.

At risk of grossly oversimplifying the entire world economy, I'll offer a very simple framework:

- Debt is unwise when it is used purely for short-term consumption.

- Debt is wise when it is used to enhance long-term economic opportunity.

Let's look at three scales of organization to see how this plays out in practice: personal , business, and sovereign.

- Personal debt

Most individuals or families have credit cards, or they've taken out a loan for college, a new car, or a house. Unlucky individuals might owe a lot in medical bills. The main consequences for not repaying are accrual of interest, dealing with annoying debt collectors, damage to your credit score, and, in extreme cases, foreclosure of assets and garnishing of wages.

Wise debt :

- If you take out a student loan, and your college degree helps you land a high-paying job, this is a wise investment. Ideally, you pay back the loan as soon as you can afford to, to avoid accumulation of interest.

- If you've fallen on hard times, and you take out a credit card, you can stave off complete calamity (starving, lacking transportation, getting evicted) until your income improves.

- If you take out a personal loan for a car or a house, you can ultimately save a lot of money in the long term (that would otherwise get wasted on Uber rides or rent payment)

- If you experience a medical emergency, and are one of the unfortunate many who are uninsured, going to the hospital is better than dying or becoming crippled long-term (both which prevent your ability to work in the future).

Unwise debt:

- If you take out a student loan, but you still can't land a high-paying job after college, then it probably wasn't worth it, financially speaking.

- If you take out a credit card, and you just use it to buy luxuries you can't afford, this is a terrible idea. Interest accrues, and you quickly get into a large debt hole that is very hard to recover from. (This needn't reflect on your character; this is pushed on us socially and culturally, and we've all been there, especially when we're young)

Any time you incur debt that you can't pay back within short order, interest accrues, and you risk damaging your credit score, or having your stuff repossessed. This is a bad situation to be in.

Business debt

Loans are an essential mechanism for businesses to make money and operate smoothly. New businesses may take out a bank loan as startup capital for their new enterprise, or they might raise debt financing from a larger investment firm, to cover fixed costs (buildings, machines, or other startup expenses), which then pay for themselves over time. They'll usually have things like a business plan, legal incorporation, a structure for managing assets and liabilities, and collateral on the loan. In addition, almost all businesses rely on a steady stream of short-term loans, to keep inventories stocked and flowing; since customers buy things from you after you purchase raw supplies from someone else, businesses are constantly taking out and repaying loans to bridge the time gap between purchases and sales.

Much like personal loans, typical consequences for lack of repayment include bankruptcy, liquidation of assets, forfeiture of collateral, or, in some cases, legal liability. One difference between business and individual loans is that there are ways to assign debt to the corporate entity itself, protecting the owner from personal property foreclosure (although bankruptcy is an option in either case).

Debt structures can get very complicated here, especially with large corporate enterprises. But to keep things simple, we'll look at an example of basic financing for a small, local business.

Wise debt:

- When your business plan is solid, and your business generates profitable returns, it's generally a good idea to have taken on debt.

- If your business model has proven itself reliable and successful, and you're generating real value for society, you might be interested in taking on even more debt, to expand your operation, solidify your market position, or to open new franchises.

- If some unforeseen event occurs which temporarily disrupts your otherwise-successful business from making money (for instance, an economic recession causing global demand to drop), loans can be essential to surviving until economic conditions improve, when costs can be recuperated and the loans fully repaid.

Unwise debt:

- If your business model isn't profitable, or even fails to generate enough revenue to cover costs, taking on debt is unwise. Creditors know this very well, so you're unlikely to be able to secure loans unless the fundamentals of your business plan is solid. The risk / reward calculation of investment is a core idea in finance, so much depends on the savviness / foolishness of individual investors; but even taking "stupid money" to finance an ill-concieved enterprise usually doesn't end well for anyone involved.

- As stated above, the main difference between personal and business debt is that, if the business goes sour, investors are typically unable to recuperate costs from the business owner personally. So substantially more care is taken when evaluating business loans over, say, letting a risky individual take out a credit card, for which a predatory company can extract a great amount of interest payments over that person's life.

- Equity finance bridges this gap somewhat, and is much more risky than a safe loan secured by collateral. Venture capitalists accept this risk, and balance it over a large portfolio of investments, with many losers but a few very-profitable winners.

- Maybe your business model is currently profitable, but longer-term trends in marketing or technology reveal that this success is just temporary. Maybe your business is built on an ephemeral trend, like a clothing style that is currently in fashion, or a political message that is currently trendy. Maybe your primary customer base currently has a lot of disposable income, but later on, their income lessens, so they stop buying your product or service. Or perhaps your business is built on an old technology, that gets displaced by a more efficient alternative that seemingly comes out of nowhere (like what happened to Kodak with the rise of digital cameras). All sorts of market forces are always at play that affect your bottom line; failure to recognize them, address them, or shift your business in response is a cause of many business failures.

- Your long-term business model may be solid, but many other factors can cause your business to fail anyway. Maybe a competitor replicates your business model and steals your customers out from underneath you. Maybe a local newspaper runs a story about how unclean your store is, your personal behavior as an owner, or about some externalities of your product that come to light (maybe your business causes pollution), and customers decide to boycott you. Your business might generate steady revenue, but you have failures at the business strategy level, debt can be unwise for both you and investors.

- From the investor's point of view, lending can be a poor decision due to the idea of "opportunity cost"; maybe you can generate stable 5% returns on one business, but if you have the opportunity to invest in another business that generates 10% returns, you should probably choose the 10% business (if you want to maximize your return on investment)

Many other examples. Running a successful business is a very challenging enterprise, and there are many books, theories, and accounts of the various pitfalls that plague both business owners and investors. All financing involves the assessment and calculation of risk, and even the most stable of businesses are always fighting external trends and forces that threaten their bottom line. Success is never guaranteed.

Sovereign debt

Here we get to the meat of the question. Is government debt good or bad? Hohhhhhhh boy. Strap yourself in.

Governments issue debt in the form of treasury bonds. Anyone can purchase a treasury bond, which accrues interest at a fixed rate at the time of purchase. These treasury bonds are how modern governments finance spending; instead of waiting for taxes to be collected, the Treasury department raises money by selling bonds, spends whatever they need to for their fiscal budget, and then collects tax revenues later to close the gap (similar to short-term loans for business inventories). If they spend more money than they raise in taxes, this is called a deficit, and the carryover gets added to the national debt.

This process is mediated by some kind of central bank, which is responsible for managing the creation and distribution of currency in which these bonds are denominated. Modern central banks control the monetary supply by setting key interest rates, buying bonds from the federal government, and doing a ton of other stuff to balance the financial system as a whole. The specifics of this get very complicated, and depend on the country in question, but the main takeaway is that a country's Treasury department (which manages the fiscal budget) and the country's central bank (which manages the monetary supply) are inextricably linked (we'll go over the issues of currency and monetary supply broadly in part 3).

The subjects of taxing, spending, national debt, and monetary supply are central to political economy, and the conflicting values, priorities, and beliefs of citizens and policymakers are causes of perpetual political consternation in every nation-state. The rest of this essay series will be devoted to exploring these issues head-on. There are exactly zero easy answers, and much depends on what you, the citizen, feel is best for your values and the continuation of society as a whole. I can only elucidate on some of the history, the status of the present moment, and some of my own ideas about the future.

Many contemporary pundits make the claim that government debt is entirely unlike personal / business debt. Are they right? Well, both yes and no. Governments are on a completely different scale from smaller entities, and they have a vastly expanded set of powers and authorities to work with. A nation-state doesn't simply go "bankrupt" like a regular commercial actor; the state experiences a sovereign debt crisis, which spills out in global politics and history as a cataclysmic event. Especially given how globalized and interconnected the world economies are, the dynamics of the consequences of sovereign financial mismanagement are flatly impossible to conceive, determine, or predict with any degree of confidence (although we'll go over some historical examples later).

But I would argue that the essential dynamic is exactly the same. Government debt is wise when it grows long-term wealth, and government debt is unwise when it merely extends current consumption, or it is directed toward risky, ill-advised investments. The mechanics of how this ultimately plays out, however, are vastly more complex than our simpler discussion of personal and business finance.

Let's start with the upside; when is it wise, economically, for a government to take on large amounts of debt? There are at least four different commonly-stated purposes for doing so. To understand them, we're going to have to delve into some industrial / military history, compare experiences across different governments, and examine a little bit of theory. It'll be fun, I promise!

The reasons we will look at are:

- Increase long-term industrial capability (supply-side stimulus)

- Pay for a necessary war (foreign policy)

- Stimulate the economy during a recession (demand-side stimulus)

- Broadly improve infrastructure, healthcare, and economic productivity (civic capital)

Increasing industrial capability

Public debt is good when it leads to increased fixed capital formation -- in other words, investment -- in long-term productive capacity. The history of industrialization, broadly, informs a great deal of thinking about investment into fixed factors of production (factories, equipment, and the like), so it's important to go over if we want to understand how we got to where we are today.

But let's start with a toy example. Consider the case of an undeveloped economy. Let's say 80% of your country works in agriculture (much like the United States did in 1800, before the industrial revolution kicked in). A rich foreign power has discovered advanced technology that makes farming 10x more productive; you learn that 90% of your labor force could be freed up to engage in higher pursuits, like education, entertainment, manufacturing, or child/elderly care. The foreign power agrees to loan you a large amount of money (billions of dollars), at a reasonable interest rate, to modernize your industries, build new factories, improve your workforce productivity, etc.

Is this a good deal? Of course -- it depends! (As we'll go over in part 3, the results of this kind of arrangement have been extremely mixed). But this example illustrates the logic clearly; taking on debt to make smart investments in productivity and industrial capacity has a high potential to improve standards of living, prevent famines and poverty, and foster all sorts of social good.

Industrial countries had to kind of do this themselves initially. The period of industrialization, when new technologies and productivity enhancements gained steam (heh heh), illustrates several case studies in how different economies and cultures reckoned with these revolutions in agriculture, manufacturing, transportation, etc. As with everything, the results were mixed, and the process was often extremely painful for both the financial system and for individual workers who had to adjust to new working conditions and new forms of competition from larger and more powerful corporations.

Of course, there was no advanced foreign power to lend money directly to would-be industrializing economies. In the American example, the financing of new factories and technologies relied on two factors:

1) Individual industrial titans, like Rockefeller, Mellon, Carnegie, Ford, et al. Depending on your perspective, they were either self-made "captains of industry", nobly pursuing the American dream and advancing civic society, or they were already-wealthy "robber barons", exploiting the labor class for personal gain, while greedily hoarding political and economic power through unfair monopolization schemes. Regardless of your perspective, these individuals were ruthless in both pursuing both efficiencies of scale, and saving every penny of profit to reinvest in their own enterprises. This is the "hard way" to enhance productivity; saving actual profits to build new factories, expand your business, etc. It is slow, painful, and probably forces you to be callous and cruel (to both your competitors and your own workers) to pull off successfully.

2) A rudimentary system of fractional reserve banking, adopted by many central banks since the 1600s, which functioned as a pseudo-expansion of the monetary supply, providing credit to corporations and developers without requiring every note to be backed up by a corresponding quantity of real assets. Before the era of "modern" central banks (like the Federal Reserve) and fiat currencies, bank notes still relied on the gold standard; you could take your money to the bank and trade it in for gold at any time. Banks soon realized that, since only a few people would do this at any given time, they could lend out some multiple of paper currency (keeping a "fraction" of total supply in real gold reserves), charge good interest rates, and ultimately end up making more money back. (This worked well, until it didn't; the 19th century was ripe with banking panics. As the value of currency fluctuated, sometimes people surged in to reclaim deposits, which banks were unable to fulfill, causing people's trust in the currency to drop precipitously. This is also known as a bank run, which you might be familiar with from movies like It's a Wonderful Life).

It's worth emphasizing the fact that sovereign debt itself played a negligible direct role in most countries' transition to a high-productivity economy (although the history here is fascinating, and there are good arguments that government bonds played important indirect roles). But the history is worth talking about, as this period is what cemented many ideas about investment, debt, and productivity generally into popular and political consciousness.

Should governments actually invest directly -- incurring large public debt -- into fixed capital formation? This is a very hot question, with mixed results everywhere. The consensus from Western countries seems to be a resounding "no" -- direct investment is the job of the private market, and the government should not be in the business of picking winners and losers. Data from the experience of Asian countries, however (notably China, India, Korea, and Japan), seem to indicate otherwise; for some reason or another, those governments seem to have been vastly more effective with their direct investments into high-productivity sectors. We'll look at this question in-depth in part 2.

In summary, though, sovereign debt can be useful when it is directed toward smart industrial policy, or when it can make the right investments in productivity growth.

Financing war

This one is fairly simple. Wars are costly. Typically, you want to win them. So you gotta pay for them somehow.

Let's start again with a simple example. Your country gets invaded by a hostile foreign power. You either defeat them, or you die. The spending calculus becomes very simple; you either raise enough money (to pay for troops, rations, munitions, supplies, equipment, and vehicles), or you lose, and concerns about economic livelihood simply don't matter anymore. If you don't have enough money, you have to borrow it (either from your own citizens, or from friendly foreign powers). Simple, right?

Hahahaha. You should know by now that nothing is ever simple with economics! Of course you still have to care about debt. Going bankrupt is almost as bad as losing the war; indeed, a debt crisis is usually the main way that countries actually lose wars. The main factors of how much debt you can raise are things like: How much strain can your citizenry actually tolerate? Who do you choose as creditors, and what concessions will they want you to make? And what do you actually spend your money on?

As we'll see with the example of Florence in the 15th century, and indeed most wars before the industrial revolution, money spent during wars usually just meant money down the drain. If all of your money just goes to mercenaries, then the people who are *actually* financing the war (usually wealthy nobles) are *actually* the ones who win the war; in Florence's case, the Medicis. There's a neat equivalence here.

Of course, there's a flipside to this. If you're savvy and ruthless with choosing creditors, you can cheat the dice a little bit. Consider the American revolution; Britain was vastly more wealthy than the fledgling American colonies, but we were able to pull through by convincing France and Spain to finance the war on our side. France, in particular, hated the British so much that they matched British spending, went bankrupt themselves, and then collapsed; afterward, the French citizenry was so inspired by the American revolution that they chopped the heads off their own monarchy, then chopped their own heads off, and then dissolved into chaos for a full decade. To add even further insult to injury, the new US state defaulted on their debt to the new French state almost immediately after both were formed, sparking another crisis. This was the Looney Tunes era of sovereign finance.

These examples illustrate that, at least before the industrial revolution, war was mostly a zero-sum enterprise: You spend money to survive, but even if you win, your economy is hurt (due to lost population / destruction of property). Or, if you're an aggressor, the amount of wealth you gain in spoils is equal to the amount plundered.

The industrial revolution changed that. As military technology (like guns, vehicles, and bombs) became increasingly determinate of military outcomes, so too did the industrial production and supply lines (oil, steel, manufacturing, distribution) needed to utilize it on the battlefield. Suddenly, wars become much more about resources, technology, and economic strength than they did about raw numbers, valor or tactical prowess. And so too changed the relationship between wartime and peacetime production; war became "profitable" in ways beyond the value of plunder and spoils.

There is no clearer example of this in world history than America's economic and military dominance during World War 2. Even before the US officially entered as a combatant, it supplied allied troops with a huge influx of food, oil, raw materials, weaponry, and warships through its "lend lease" programs; while, at the same time, establishing an oil embargo on the Japanese empire (prompting the attack on Pearl Harbor, and officially drawing the US into the war).

To fund the war effort, the US took on an incredible amount of public debt, notably in the form of war bonds; the government embarked on a patriotic advertising campaign, imploring US citizens to contribute, and raised over $180 billion in today's dollars to finance production. Debt-to-GDP rose to its highest levels in history, a historical peak of ~122% (well, before this year, at least). To this day, this whole-of-society war effort remains a high point in American history; we built the gear, beat the Nazis, and the rest is history.

Particularly notable for the economy is what happened after the war concluded. All of that industrial capacity and technological prowess stuck around, and the post-war boom cemented the US's stature as a preeminent world power. Several factors contributed this; not only could we continue to manufacture military equipment and munitions (to sell to other countries), the US became a hub for global scientific and technological talent (boosted by initiatives like Operation Paperclip), demand for all sorts of goods and household appliances skyrocketed, and fixed capital goods (buildings, machinery, and tools) were repurposed to produce peacetime consumer goods (refrigerators, cars, stoves, electronics, chemicals). For the next decade or two, the US manufacturing sector dominated the world economy, and the US accumulated a vast amount of real wealth.

WWII was a pivotal moment in American history for a dizzying number of reasons. It set the stage for the Cold War; it brought about "dollar diplomacy" (bolstered by Bretton Woods agreements); it transformed the American economy; and it saw the rise of new theories about economics, finance, and geopolitics. We'll return to this period again in parts 2 and 3. For now, our summary is "debt is acceptable when it fuels necessary wartime spending, preferably when it has the side-effect of increasing industrial capacity".

Stimulate demand

Here we introduce a very great man, and a truly pivotal force in world political and economic history. John Meynard Keynes, born in Cambridge, England, in 1883, is known as the father of macroeconomics; his early 20th century writings on interest, money, employment, business cycles, and other topics form the core basis of modern economic philosophy.

Besides being a prolific economist, he was actively involved in high-level statecraft. He helped negotiate the Lend-Lease program with the Americans, setting the stage for the global system of free trade that followed WWII. He sat in on the Versailles peace process, and was one of the loudest voices arguing that harsh punishment of Germans would only lead to further conflict. He worked with FDR to discuss aspects of the New Deal (although he was mostly ignored, to regrettably ill effect). He was kind of like the Forrest Gump of 20th century geopolitical affairs. Personally, he is one of my favorite philosophers and diplomats, and his ideas and political work are essential to understanding how the industrialized world developed between and after the world wars.

In the context of our current subject -- the wisdom of raising debt -- Keynes identified a crucial variable in the functioning of an economic system known as aggregate demand. While the last two points have focused on the "supply-side" of the equation (increasing the amount of stuff made), this idea revolves around the "demand-side" of economics (increasing the amount of stuff people purchase). We'll begin, as always, with a simplified model.

Keynes' ideas theory of aggregate demand begins by addressing natural business cycles, also known as "boom-and-bust" periods. It was long noted that capitalist economies had periods of exuberance, when commerce flowed freely, and had periods of recession, when economic activity dropped and people stopped buying things. While people greatly enjoyed reaping the benefits of the boom period, the bust period was often painful; particularly painful given the rudimentary fractional-reserve system, common in the 19th century, that we discussed earlier. People generally understood that having excess credit floating around in the system (having more paper notes than actual gold reserves) was a good thing for investment, productivity, etc. But when people recognized that certain assets were overvalued, and the credit crunch came, the various panics (bank runs, general commercial fear) and resulting financial insolvencies caused many serious hardships and crises.

In 1936, Keynes published the General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money, which sought to address the extremes of the natural boom-bust cycle in a way that both tapered off exuberance when times were good, and also cordoned off the ills of panic and recession when times were bad. His key insight was that government spending -- particularly, being okay with large temporary deficits -- were essential to keep the economy running smoothly during downturns. The basic model is fairly easy to understand, although this is where we start to get into some loopy second- and third-order effects that can be hard to wrap your head around at first (economists love this type of shit).

The general idea is as follows. Imagine your country experiences an economic downturn. Some bubble bursts, people are worried for the future, and there is a general air of fear that the economy is about to shrink. People's natural first instinct is to save money and stop buying things -- because you're worried that other people aren't buying things, times might be tough for you in the future, so you tighten your belt. If everybody has this reaction, then that means everybody saves money, and everybody stops buying things.

What does that do? It increases real unemployment. Suddenly, people are out of jobs, which means they actually do have less money, which means they actually do buy less things. You can see where this is going; an economic downturn is both a vicious cycle and a self-fulfilling prophecy, which feeds off of people's fears about the future to reduce economic activity to a halt. If this continues unabated, it can cause an economic depression, which can last years, or even decades.

The solution to this, in the most naive version possible, is for the government to just give everybody money. Poof. Make $1,000 out of thin air, put it in everybody's pockets, and reassure everybody that everybody else has enough money to buy things from everybody else. Alternatively, the government can finance large public works projects, offering employment directly to people whose incomes have been disrupted by hard times. In practice, this actually does seem to work fairly well at stymying negative feedback loops and increasing customer confidence. Whenever you hear about governments running a "stimulus" program, they're channeling Keynes' ideas directly.

Of course, to pull this off correctly -- without causing other adverse effects -- a number of conditions need to be strictly adhered to:

- Aggregate demand stimulus should be funded purely through raising debt. Raising taxes during a recession is very counterproductive; it prohibits customers from spending, and it prohibits businesses from paying their workers enough to keep spending.

- There should be as little interference in normal market operations as possible. Restricting output, artificially lowering / raising prices, or crowding out private sector investment all distort natural market mechanisms, preventing a true recovery.

- Stimulus, in the form of direct payment, should be directed to consume domestically-made goods as much as possible. If the new income is spent on foreign goods, you miss the point of increasing domestic employment entirely.

- After the economy recovers (and *only* after the market recovers), taxes should be raised to cover the debt incurred, to balance the budget and prevent inflation. If inflation / debt is already too high, citizens should be encouraged to save and spend very conservatively, instead of borrowing even more and exacerbating the problem.

- As a bonus, but not strictly necessary, your debt-funded stimulus should ideally go toward projects and business that generate good ROI in terms of future growth. It's pretty hard to organize investments that generates long-term value on the short timescales that stimulus decisions operate on, but a very savvy government could probably do really well here (maybe by lining up valuable public works projects in advance)

Funny enough, although many of Keynes' ideas have permeated the economic discourse and decision-making of world governments, there exist virtually no examples of governments actually following the above guidelines when trying to implement a Keynesian stimulus program. Even the New Deal, often cited as the most prominent application of boosting aggregate demand, was fraught with issues (that Keynes himself pointed out) which may have inhibited recovery, extending the Great Depression longer than it should have gone on.

But anyway, that's another subject 😅. To summarize this section, though; it may be wise to incur public debt in order to boost aggregate demand in a nasty economic downturn, shortening the bust cycle and staving off long-term negative effects.

Increase civic capital

Finally, the last case for when governments should theoretically take on new debt involves improvements to what I'll call "civic capital". This includes two broad categories -- construction and maintenance of physical infrastructure (such as highways, utilities, and internet equipment) as well as improvements to human capital and productivity (such as health, education, and civic capability).

Everyone understands the need for physical infrastructure, so I'll keep this section brief. It's generally seen as positive for governments to take on the procurement of neutral infrastructure -- also known as "public goods" -- as a common basis for supporting commerce and the necessities of basic life. Every citizen should have access to clean water, stable electricity, high-speed internet, reasonably maintained roads, waste removal, and other sorts of life necessities, without the discrimination and competitive stress that comes with private enterprise. Of course, this issue is never clear-cut; there will always be debates over what should count as a public good, how they should be funded, which jurisdiction is responsible for them, et cetera. But the idea that there should be public goods is generally accepted by everyone except the most ardent libertarians.

The more contentious issue is the role of government in procuring advancements to human capital; fostering healthy, happy, educated, and economically productive citizens. But before we continue, we must pause here to make clear an absolutely critical point about philosophical ontologies.

Human capital is foundational in the study of economics, but it is important to note that it is very hard to talk about in objective, detached terms; human beings are infinitely more than mere factors in an economic system, and when we discuss their livelihoods, we have a tendency to make a severe conflation between very different types of philosophical thinking. Typically, we confuse a system of ethics -- what is good, virtuous, noble, etc. -- with a system of material allocation, which is the study of economics. Economics does not, cannot, and should not make any explicitly moral claims about what is "best" or "the right thing to do". Economics merely concerns itself with the question; given that we have values, goals to pursue, and material needs and wants, how do we best pursue those ends efficiently, fairly, and sustainably?

Philosophy, unfortunately, is not an exact science. It is actually impossible to separate these questions completely, to everybody's satisfaction. All we can hope to do is factor out the foundational issues of ethics and values as much as we can from the discussion, and try to uncover as much common ground as possible, which we will try to do here and in the rest of this essay series. If you notice any economic claims that actually sneak in a subtle moral claim, you have full right to call it out and demand a debate about it. We'll return to this briefly near the end of the essay, but for now, let's try to discuss human capital in the objective, dismal, instrumental terms that the study of economics warrants. If this discussion makes you think I'm a monster, I totally understand.

The biggest debates in modern capitalist democracies usually center around healthcare and education. Unlike physical infrastructure, which is relatively inexpensive and non-controversial, these types of social public goods typically represent a large fraction of a nation's GDP, and, as mentioned, allocation of these goods and services involve deeply-held differences in values and beliefs between citizens' views of what an ideal society should do (not to mention what role the state should play in it).

Let's start with healthcare. When we discuss worker productivity, the central unit of analysis is, of course, workers. The worst thing to happen to worker productivity is that the worker dies; if a worker dies, they will no longer be able to generate value for their soulless capitalist overlords. All of the skills, childcare, education, and other investments in their growth as a worker will be lost. It is a terrible thing to happen….purely in terms of the flourishing of our precious economy, of course.

The second worst thing to happen to worker productivity is that a worker gets crippled, sick, depressed, addicted to drugs, or otherwise becomes unable to work to their full potential. In the worst case, this can be nearly as bad as dying; if you're disabled, you cannot generate value for your soulless capital overlords, and this too is a very bad thing from the standpoint of our precious economy.

The third worst thing to happen to worker productivity is that workers suffer from long-term, chronic, and otherwise preventable conditions that also hamper their ability to produce economic value as they get older. Long-term damages to one's body (say via poor posture or spinal strain) in their 20s and 30s make them unable to perform manual labor in their 40s, 50s, and early 60s. Poor nutrition and exercise can lead to heart problems, brain problems, and digestive problems. Poor mental health can cause one to become discouraged, unmotivated, or even burned out. Smoking of cigarettes can lead to other cardiovascular problems, or lung cancer [Note; I'm 100% guilty here, this essay has taken me a carton to write so far]. The list goes on.

One important factor to note about this third category is that, not only do these "preventable" issues hamper productivity in the long-run, they also become extremely expensive in terms of net healthcare costs, as one gets older and requires the use of more and more medical services. In all but the most callous of societies, we choose to take care of these people anyway, even if they become no longer economically useful.

These are the main public health issues that plague the economies of advanced, industrial societies. But it is also worth examining some edge cases, particularly in the field of development economics, to get a full picture of just how important health intervention can be for a fledgling economy. In undeveloped countries, one of the central factors impeding the industrialization process is the development of children. Malnourishment, child mortality, the spread of infectious disease (which have long been cured or prevented in advanced economies), and other extremely basic interventions are both notoriously absent, and go a very long way toward ensuring children have a shot of getting through the education process and participating in the amenities of modern quality life. While we have made some huge strides toward the elimination of global poverty and destitution over the last century, there's still a long way to go, which is why global charitable causes still have such a high ROI, in terms of both preventing tragedy and increasing the global standard of living.

As such, one important role of governments (and one economic justification for taking out debt) is the fostering of public health. The government should be interested in making sure that workers are healthy, happy, and productive. And they are arguably in a privileged position to make sure this process is managed effectively and equitably, over competing private or philanthropic enterprises. What the state's ultimate role should be, and how they should go about it, is a question of both policy and morality, which are outside the scope of this discussion.

Finally, we should consider the role of education in worker productivity. This is somehow even more hotly contested than healthcare, so we'll try to avoid getting into the many moral and political entanglements that modern education discourse often finds itself in.

Fortunately, for the purposes of economics, the role of education in pure worker productivity is actually a lot more minimal than you might expect. Most jobs, even in advanced economies, don't actually require much basic knowledge to perform; for blue-collar labor in particular, you can get by on rudimentary levels of communication skills (reading, writing, language, and computer use), math (arithmetic, algebra, geometry), and a basic survey of physics, accounting, critical thinking, etc. Specializing in a technical vocation afterward is also necessary, but need not be part of the core education process.

Most of the value of the education system actually comes from less from the acquisition of essential knowledge, but from the other "soft" factors that primary education provides: Basic childcare, opportunities for socialization, learning to obey rules / authority figures, practice with exercise / nutrition, reprieve from abuse at home, and basic introduction to civic factors (like history and politics). These functions form the bedrock of acceptance of primary education as a necessary public good, one that every citizen has a right to participate in equally.

While the value of universal primary education is pretty much unanimously agreed upon, things get much tricker when we start to discuss secondary education, particularly in the context of white collar sectors. Here the picture is substantially less clear. While there may be some arguments that it qualifies as a public good, this is nowhere near universally agreed upon, so we won't discuss it here (but we will touch on the accounting aspect of it in part 2).

One final thing to note about "civic capital" and public goods, coming back to our original discussion about the wisdom of sovereign debt. In most advanced economies, the basic procurement of these services are usually already established and generally agreed-upon by its citizens. While the cost of maintaining these institutions can be quite large, it can usually be financed by ordinary tax revenues. There is rarely a need for new, large investments to be made by raising a bunch of new public debt (although solid cases can and do get made).

These issues are vastly more important in the context of development economics; if your country *doesn't* already have basic health and education institutions in place, it is very easy to make a solid economic justification for taking on huge amounts of debt (usually from foreign creditors) to leapfrog your citizenry into industrial modernity (assuming, of course, this is what your citizenry actually wants! Be careful of value judgments!). And the value that these institutions provide is always going to be an essential part of the discussion about government expenditures and revenues, even in the most advanced countries.

==

Thus ends our survey of the utility and wisdom of justified cases for the government taking on large amounts of debt. Now let's briefly mention the counter-point; when is it unwise to raise new public debt?

This section will, thankfully, be much shorter. The basic negatives are parallel to the negatives of taking on debt in a personal / business context. A public debt is unwise, economically, when it:

Doesn't increase long-term growth, but is instead used purely for short-term consumption.

- Accrues too much interest. Currently, 8% of the US federal budget goes to servicing interest on public debt alone.

Has a poor return on investment. Government spending isn't useful when it is merely allocated to initiatives that can in theory foster economic growth. The investment actually has to follow through on its goal in real terms for the investment to follow through on its stated purpose. And governments sometimes aren't the best at doing this.

Another way to view this, in the context of ordinary taxing and spending, is that each dollar the government spends (either directly through taxes, or indirectly through deficit-inflation) is one less dollar that the private sector can spend making its own investments. This debate over whether private or public investments are "generally better" is a value judgment landmine (we'll try to offer some perspectives in part 2), so it's important to just note the principle here; public investment necessarily crowds out private investment, and net investment in a closed system is conserved.

(That last statement introduces yet another tricky issue; nation-states are not, in fact, closed capital systems. They can choose to invest in one another, which brings the topic of "foreign investment" into play; another subject we'll examine in part 3).

Is not eventually balanced with commensurate tax increases, and generates inflation. Inflation, as we'll see in part 3, is bad.

Lastly, if debt gets too out of control, and you fail to even make interest payments, you risk a sovereign debt crisis.

The worst thing that can happen as a result of too much bad debt is a sovereign debt crisis. What is a sovereign debt crisis? In a nutshell, it means your country becomes unable to make interest payments on its outstanding debt, or your debt (and therefore your currency) becomes devalued somehow. A sovereign debt crisis is very bad; serious events risk unfolding that threaten societal and economic devastation. Your currency may collapse; civil unrest might reach a boiling point; a humanitarian crisis could unfold; you might become beholden to the whims of foreign creditors. Generally, if your country fails to service its debt (especially foreign debt), things suck hard economically for your country's households, businesses, and investors for a long time.

Gross sovereign financial mismanagement is another topic with a long history, replete with both clear and complex lessons, which are hotly debated among economists, historians, and politicians. The most clear lesson is: don't have one. It's another topic worth delving into if you want to get serious about geopolitical macroeconomics. I'll offer a brief survey of some of the more notable examples of public debt calamity preceding civil strife, starting all the way back in Renaissance Europe:

In 1423, Florence declared war against Milan, a longtime rival. While they ended up winning the war, they incurred so many costs paying mercenaries that they were forced to implement a wealth tax, which bled the citizenry dry. The wealthy Medici family rose to power, as the merchants with the deepest pocketbooks, eventually usurping political power over the country.

Throughout the 16th and 17th centuries, the powerful Spanish empire gradually declined into irrelevance. A leading theory for this is that a huge influx of Spanish silver and gold, mined from the new world, flooded the money supply of the European economy, causing inflation (and thus ultimately diluting Spanish economic power).

In 1772, a banking executive fled London to avoid repaying a debt, and his firm collapsed, triggering a larger panic in the British financial system; country-wide bank runs led to the bankruptcy of several other firms. This set off a chain of events that eventually affected the fledgling American colonies; as the East India Company frantically tried to sell off assets to cover *its* debts, it compelled the British government to enact new tax legislation to privilege the sale of its 18 million pound stockpile of tea to hapless new world colonists. We all know how much Americans hate British tea; it tasted so bad that the colonists threw it into the ocean, declared war on the British empire, and became a beacon of liberty and democracy to the entire world for hundreds of years thereafter.

In 1890, a series of poor investments in Argentina resulted in a bank run on London-based Barings Brothers & Co, the world's largest merchant bank, causing the first "modern" banking crisis. Barings was saved by a "bailout" from the Bank of England & other major investors (including the Rothschilds). Argentina suffered a far worse fate; real GDP was decimated, foreign investors fled the country, the currency collapsed, and coups and strikes plagued the country's political system for at least a decade.

After Germany lost WWI, the treaty of Versailles imposed severe reparations on the German people, who were already in huge debt due to the war. As the gold standard for German notes was suspended as the war broke out, and Germany's economy was too weak to repay the harsh penalties in terms of material goods, the Weimar government began printing mass amounts of Papiermark, causing hyperinflation. The price of a loaf of bread in nominal marks rose from 13 cents in 1914, to a quite hefty $100 billion in 1922, when the currency completely collapsed, along with the economic system and civil society. The Weimar government eventually followed suit, the Nazis rose to power, and the rest is history (Babylon Berlin is a great show about this period, by the way).

Things get more interesting and complicated in the 20th century. I'll stop short here, but the following episodes are rather enlightening for further research:

- Several Latin American countries in the 1980s

- The 1997 Asian financial crisis

- The 1998 Russian ruble implosion

- The 2007 Zimbabwe hyperinflation

- The rolling post-2008 crisis in Greece (this one is real Looney Tunes)

- The tragedy unfolding in Venezuela currently

To be fair, these are extreme examples. More commonly, mismanagement of fiscal and monetary policy results in the more banal harms of high interest payments, moderate inflation, corruption, siphoning of middle-class wealth, and general political consternation. But in general terms, the more mismanaged your country's finances are, the worse things can potentially get for you.

So to wrap up the meat of this essay, and to move on to the conclusion: Sovereign debt is bad when it doesn't grow the real economy, and when it fuels reckless consumption. The main consequences are taxpayer-financed interest payments, inflation, and the risk of a cataclysmic sovereign default.

==

All of this discussion so far begs the central question. The USA currently has $26 trillion dollars in public debt, government spending is currently a mess, and whatever comes out of the remaining coronavirus stimulus packages for 2020 will likely add trillions more on top. How bad do we have it, really? Is our debt burden unsustainable? Are we risking some kind of catastrophe?

Alright; we've learned a little bit about finance so far. You should know the answer by now. Ready? Let's say it together:

It depends!

Debt alone, as we've seen, is fairly neutral. The related question we haven't really examined yet is; what total magnitude of debt can one afford to maintain? This, too, is its own complicated subject, with lots of thinking and history behind it. Ultimately, it boils down to the evaluation of your current and potential creditors. What do they think about you? Have you been a good debtor in the past? Are you taking this debt out for a legitimate reason; are you doing something valuable with that money? Do you have a significant chance of paying off your interest / principal in the future?

The other two parts of this essay, on GDP and USD, explore the other critical variables necessary to make this full assessment. But for now, I'll go ahead and put my personal conclusion up front; should US treasuries be considered junk bonds?

In honest, sober truth: Probably not. The US's current position is, in total, "fine"; catastrophe is not inevitable, and there's still a good chance we can turn things around before things get totally out of hand. For all our multitude of problems, divisiveness, and myopic stupidity (which we will continue to outline in painful detail in the following chapters), the United States is still both the largest economy and the biggest technological and military force in the world. The US dollar is still a highly respected reserve currency among the world's banking systems. The US agricultural sector, in particular, is still astronomically productive, feeding every American and having enough left over to be a net exporter, while still employing less than one percent of the workforce. Land, buildings, and other physical factors of capital remain abundant, and, despite some foreign supply chain issues for a few key goods, we actually do make most of what we need to survive here in the United States. I would personally be okay with buying US treasuries as one of the safest investments available; the interest burden, while large, is still only at 8% of the total federal budget, and it's hard to imagine us not being able to pay it in the medium-term.

Furthermore, as stated, sovereign debt is very much unlike personal or corporate debt, in that a sovereign debt crisis bleeds across the boundary between economics and geopolitics. A major nation-state's solvency is an issue of critical global importance. If the US dollar crashed to zero, or the US somehow became a failed state, this would spell terrible news for our friends and allies across the world, and they are very interested in making sure that that doesn't happen. Of course, global sentiment of the United States, too, is an important variable to consider (which we will consider in part 3).

The primary issue with trying to understand this type of risk is the sheer magnitude of variables involved. The phrase "too big to fail" is not merely a hand-waving dismissal of inconvenient problems; it's actually a critical philosophical issue when it comes to epistemology. How on earth do we, mere humans, reckon with systems that are several orders of magnitude beyond our ability to comprehend?

==

You might be inclined to trust the opinion of experts. The problem of evaluating world-scale financial risk is the central question of academic finance. Many incredibly smart people have devoted a huge amount of intellectual effort to trying to understand the dizzying problem of creditworthiness in the abstract. For the most part, at the scales of personal and small business commerce, their models do a really good job. When we reach the scale of corporations and nation-states, however…things start to get weird.

There are two recent illustrations of this in the context of the post-Cold-War financial system. The first is the story of Long-Term Capital Management, detailed in the excellent book When Genius Failed. Long story short: Some brilliant PhDs came up with a new financial model for arbitraging sovereign bonds; they formed a hedge fund, made billions of dollars, almost crashed the world economy, and then crashed themselves (they were deemed "too big to fail", and the federal reserve bailed them out in the end). The Balance has a great abridged summary, if you're getting tired of my lengthy list of reading recommendations.

The other example should be familiar to all of us by now. But let's take a quick detour and talk about creditworthiness. How do financial professionals actually rate credit risk?

For personal debt, you have a "credit score" - a simple algorithm that a few companies use to evaluate how likely you are to pay back a generic debt. Their algorithms determine your fate; if they decide you're a credit risk, you're a credit risk. C'est la vie; life is hard for the individual. As Open Mike Eagle says: Don't be like me; get your credit fixed.

This credit score is determined by a ratings agency. Different ratings agencies work at different scales, but they all do the same thing; they plug your credit history into an algorithm, which poops out a result (usually a number or a letter grade) that determines your total worth as a human being. For personal loans, there are three key companies you're probably familiar with; TransUnion, Equifax, and Experian, which issue every person a number on the FICO scale between 300 to 850. For small businesses, there's also Dun & Bradstreet; business credit scores are usually on a scale from 0 to 100. For corporate and government bonds, there are also three major agencies: S&P, Moody's, and Fitch. They evaluate large corporations and governments and issue a letter grade, like B, BB, BBB, A, AA, and the highest rating, AAA (the safest bond possible).

How rating agencies determine creditworthiness, especially for larger entities, involves a shit-ton of extremely complicated statistics. Very smart people with prestigious math PhDs have developed advanced theories and models which produce unshakeable results about whether a potential bond issuer is trustworthy or not, and whether the underlying debt is "sound". If a bond is rated AAA, that means that you can be extremely sure that it is a safe investment, and nobody should ever have any reason to worry about the underlying transaction in question, that the bond issuer will remain solvent, etc. In fact, the smart people with math PhDs can assure you that it is almost mathematically impossible for these bonds to default.

…

…

…

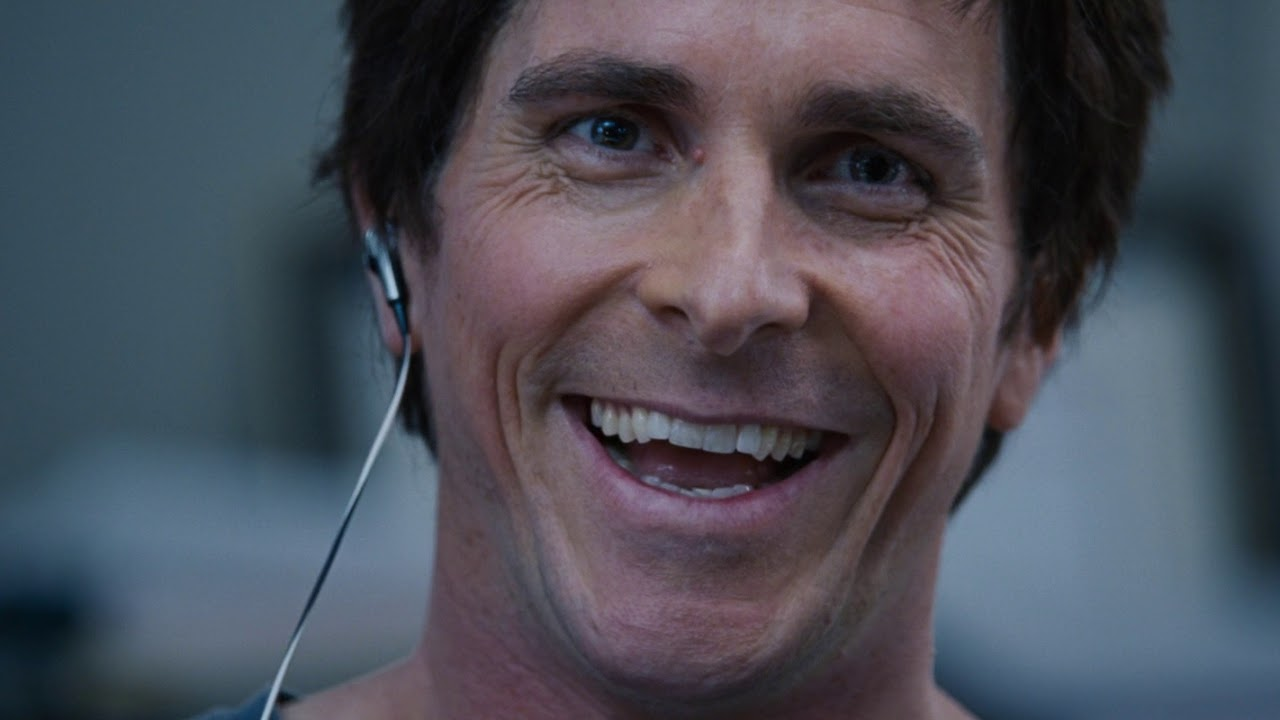

Everyone should know the rough story behind the 2008 financial crisis by now. As a refresher, I highly recommend the movie The Big Short (starring Christian Bale, Brad Pitt, Ryan Gosling, and Steve Carell). The full movie is on Youtube for free; get your friends and family together and have a movie night. It's worth it.

The world's briefest recap: In the 90s, banks started offering increasingly risky subprime mortgages to new homeowners who probably couldn't afford them. The smart people with fancy PhDs created incredibly complex financial instruments to make those loans seem safe, when -- surprise -- they weren't. Trillions of dollars worldwide were invested in mortgage-backed securities, under the belief that, even if homeowners defaulted, the home prices themselves would never -- could never -- collapse, so the collateral would still be worth the investment. Lo and behold; subprime mortgages began defaulting, housing prices collapsed, the American financial empire ate pavement, and the rest is history.

How did this happen? Well; in a nutshell, everything failed, at every level of civic society. It's really hard to describe the scope of cascading fuck-ups that occurred. Everyone has someone they prefer to blame: Rich people tried to blame the individual mortgage holders for taking out loans they shouldn't have (which quickly backfired in the court of public opinion). Liberals blame greedy bankers and congressional deregulators (particularly the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act passed in 1999, which allowed different types of financial service providers to merge into big conglomerates). Conservatives blame lawmaker Barney Frank, then-chairman of the committee that oversees Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, which are government-sponsored enterprises that stabilize the mortgage market by buying and selling distressed home loans. Academic mistake-theorists assign blame to nobody, but to a glut of global investment capital that had nowhere else to go. Everyone seems to blame Alan Greenspan for some reason (I actually like Alan Greenspan; The Age of Turbulence is a great boo… okay, I'll shut up now).

I think a large portion of the blame, though, goes to the field of academic finance. The main reason that this crisis "came out of nowhere" and "blindsided everybody" is that we, collectively, put too much faith in mathematical experts. Lewis Black pretty much nails it here:

I knew that we were heading to the shitter. And I know nothing. And I knew. And I can guarantee that, everybody in this room who had a job, working 40 years a week, a year before the shit hit the fan, you were sitting in the office; and either you said it, or someone in your office, at some point, turned to you, and went: Uhhh. I think we're fucked.

Experts are sometimes right about things. Sometimes, they aren't. Overall, what our system lacked, at every scale of society, was civic judgment. And in a democracy, the ultimate responsibility for the flourishing of our economy doesn't lie with politicians, or bankers, or regulators, or academic know-it-alls. The responsibility lies with you.

==

I really don't want to be too alarmist about any of this. 2008 is an extremely different time from 2020; Bear Stearns is not the US treasury department. Anyone telling you to panic is wrong, because not a single person on earth can predict with any sort of certainty how chips may fall. It's entirely possible that things will remain perfectly fine, we avoid another major financial crisis, and we recover from 2020 and coronavirus with a renewed sense of civic unity.

The purpose of me writing this series is not to just proclaim inevitable doom, or to cause mass panic, but to draw attention to the fact that our continued success is not some kind of inevitable truth of history . The long-term trends of existential polarization, runaway consumption, geopolitical blindness, and senility of basic economic history are severely worrying -- *have been* severely worrying for a while. The longer we dawdle, the shorter of a time scale we have to act. The sooner we educate ourselves, agree on basic reality, and repair our nation's economy and finances, the better.

While I think many pundits, economists, and leaders share my basic assessment about America's current economic position, they seem to refrain from trying to educate people about it, and they rarely advocate for change in the mainstream public discourse. I can only guess at three reasons for this: One, they don't want you to worry needlessly about it. Ordinary people probably shouldn't have to constantly grapple with this crap to live normal, productive lives. Technically this type of education is the job of the media and universities, but we'll leave those as topics for another day. Two, they have a deep cynicism that the American people are fundamentally just too stupid to understand and reckon with reality. It's hard to not succumb to this cynicism. But I'm optimistic; people are actually very smart, empathetic, and capable, when you give them a chance. And we've never had the internet before; this essay itself would have been impossible to distribute just a couple of decades ago.

The third reason, and probably the most scary of all, is that perhaps they are just literally senile themselves, and have deluded themselves into thinking that the US financial system will remain dominant on the world stage until the end of time, via some sort of cosmic providence. I don't know what to say about this, other than the participation of young Americans in political and economic discourse is more important than ever.

As we dig into the economy and the US dollar in the upcoming segments, I want to leave on one final note. And that is about values.

As we've stated, economics is a totally separate discipline from ethics. Everyone is always going to have different ideas about what is best in life, and what the right thing to do is. These debates should be a healthy and normal part of a functioning liberal democracy. But economics is really freaking important. No matter what your values are, or what you want to accomplish, or even your beliefs about big government or hardcore socialism; nothing matters unless you can marshall the physical resources to achieve your own ends. You can only exact as much justice as you can afford. Going broke doesn't help anybody. If the system becomes insolvent, everybody suffers, the disprivileged and vulnerable most heavily.

In the 20th century, the field of pure economics has gotten deeply wrapped up in some incredibly wack ethical (and even metaphysical) systems of thought. I think this has caused a great deal of confusion. On the other end, the discipline of economics has also somehow become weirdly disconnected from the discipline of politics (there used to be a field called "political economy", in which this type of analysis was commonplace). Our ontologies are just all super mixed up, and it would behoove us to think more clearly about which claims belong in which argumentative bucket.

So I'll give one big up to the MMT crowd. As an economic philosophy, MMT is hogwash sophistry (it's just restating Keynes' ideas with a fancy sheen around it). But as a moral philosophy, and as a civic statement, I think they are grasping something deep about our society, our values, and the nation we want to live in, that many anti-socialists fail to understand. Whatever political solution we come up with to meet the challenges of 2020 and beyond, it must include an authentic, sweeping, and effective plan to raise the station of the bottom 20% of society. Nothing else will work ethically, and nothing will improve civically, until we start treating every American citizen with the moral worth of a full human being. Economic and racial disparities must be addressed. It should be okay for every American to say that black lives matter.

This concludes our exploration of public debt. In part 2, we're going to take a hard look at the economy. What even is our economy? What do we actually produce, and what kind of value does our labor provide? It all starts with a classic joke: Two economists are walking in a park...